Research activity

Mission Microbiome: two months in the Atlantic Ocean aboard the schooner Tara

This is the story of a unique and exciting journey, aboard a sailing boat called Tara, of the TaraOcean foundation. The adventure begins in a research center in Chile, precisely in Punta Arenas and ends in South Africa, in the chaotic Cape Town, passing through the Falkland Islands, the remote South Georgia and the endless Atlantic Ocean.

The IDEAL center in the Chilean Antarctic Territory and the shadow of Covid-19

Before setting sail for the open ocean, scientists and crew members about to board for the mission were housed in the “Center for Dynamic Research of High Latitude Marine Ecosystems” (IDEAL) in Punta Arenas (Chile). This is an opportunity not only to settle in before departure, but also to familiarize with the scientific protocols, the spaces and the material on board. In addition to learning the protocols of the mission, at the IDEAL center I met my adventure companions, tasted typical local dishes, one above all the “King Crab” proudly cooked for the occasion by one of the Chilean leaders of the center. At first, as always on the eve of an oceanographic cruise, I was both excited and agitated. Not only because this was the longest expedition I had ever participated in, but also because I would have been away for two months in the middle of the ocean aboard a 30m sailboat! and I was the first Italian to take part in this expedition (the Mission Microbiome. All this was really exciting!

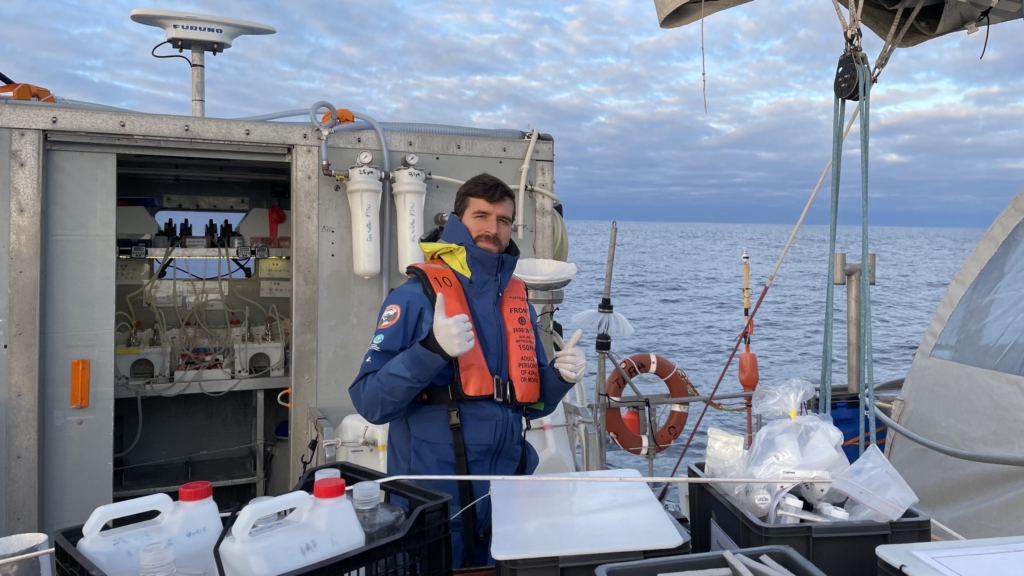

The oceanografic cruise I was about to join was part of the Mission Microbiome, an expedition that for nearly two years would have travel around the globe studying the benefits of the ocean microbiome and its interactions with the climate and pollution. During the expedition, I was in charge of the biogeochemical protocols and filtrations with the 47mm system (the diameter of the filters used during the filtration process) for nanoplastics, metabolomics (a technique that gives information on the small molecules produced by the metabolism of marine microorganisms), particulate organic carbon (POC), particulate mercury, environmental DNA (eDNA) and obviously dissolved organic matter (DOM).

Departure: the furious fifties, the Falklands and South Georgia

At the first light of dawn on a cold and cloudy March 4th, Tara, left the bay of Punta Arenas and ventured to the Strait of Magellano. The greenish and nutrient-rich waters of the strait soon gave way to an intense blue, that of the Atlantic Ocean. During the first few days at sea, time passed slowly between a lesson on safety on board, one on sailing and another on reviewing sampling protocols. The sea gave us a bit of calm, an initial momentum, a sort of gift for the first days of sailing, well accepted by all of us who were trying to get used to the slow and constant movements of the boat which would cradle us for the following two months.

Flocks of great cormorants (Leucocarbo atriceps), followed the wake of the sails, all in formation. Curious and agile, Commerson’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus commersonii) popped up from time to time, surfing above the waves created by the ship’s keel. A juvenile humpback whale in the distance beat its tail on the surface of the water to stun the krill, abundant in those waters, before eating them. We left the land a few days before, but the spectacle of the uncontaminated nature of these waters, worthy of a National Geographic documentary, was not long in coming!

As the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) approached, the seas began to get rougher and the winds stronger. It was only a matter of time, we were on the 50th parallel, where strong westerly winds, called “furious fifties”, usually blow between 15 and 25 knots. I remember in those days, at full sails, the boat leaned on its side and began to slide on the waves, like on a surfboard, it was at that moment that I realized what it really means to go sailing. The silence without the engine running, the sound of the waves and the wind to accompany us. The true essence of going by sea, in close contact with the ocean.

Arriving at the Falkland Islands, the strong wind forced us to take shelter in a small bay for a day and a night before resuming the open sea, towards South Georgia. Although the wind had dropped slightly, the sea gave us no respite and forced most of the scientific team, myself included, into an unconditional surrender. Lie down on the cots, with our eyes closed and the stomach twisting, waiting for everything to pass. As a precaution, we kept next to us a bucket with a smiling face drawn on the bottom, just to lighten up and laugh a bit about it. On board began a sort of sale of bananas, highly recommended food in these cases, and pills against seasickness. I remember that the first night at sea in a storm, I was on watch from 4 to 6 in the morning, one of the most demanding shifts. With two other crew members, we went to hoist the headsail, called the Yankee. Fumbling at night, with the spray of freezing water and the cutting wind at every jolt of the ship was both evocative and frightening. Fortunately, the crew members, much more accustomed than us to stormy seas, took matters into their own hands until we too began to get used to it. And here, after a few days at sea in a storm and carefree sailing, in the middle of a thick fog, the first rocks of South Georgia appear. To welcome us, the albatrosses (Diomedea exulans), as if to welcome us to their earth.

The experience in South Georgia was really exciting. We had the opportunity to visit the largest colony of king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) on the island, to admire the beauty of the fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella) from a few meters away, the majesty of the albatrosses and the clumsiness of the elephant seals. Moving agile and fast among the islets, we sailed to the foot of a glacier that touches the sea. We had the opportunity to accompany the researcher Alice Poncet, our guide during our trip in South Georgia, to count the albatrosses, an essential procedure to monitor them. But the visit to South Georgia was also a moment of intense reflection, linked to the memory of the whalers, who brought several species of cetaceans and seals close to extinction in these islands, as well as endangered the fragile ecosystem of the island by importing alien species, mainly rats and reindeers, the latter having become one of the symbols of the island.

In the heart of the Microbiome Mission: chasing eddies in the boundless Atlantic Ocean

With South Georgia behind us and the wind in our favor, we began to really get into the mission. Our goal was to be able to identify and to sample inside, outside and at the edge of one or more ocean eddies (an eddy is an oceanic structure, a large vortex of water current tens of kilometers wide that moves in clockwise or counterclockwise). The eddy that we had identified was named for the occasion “Sally” in honor of the researcher Sally Poncet, our guide during the South Georgia trip. Choosing the exact location of the sampling stations was not easy, there was an intense coordination work between the scientists on board and on the ground, who sent us satellite information on the position of the possible eddys in almost real time.

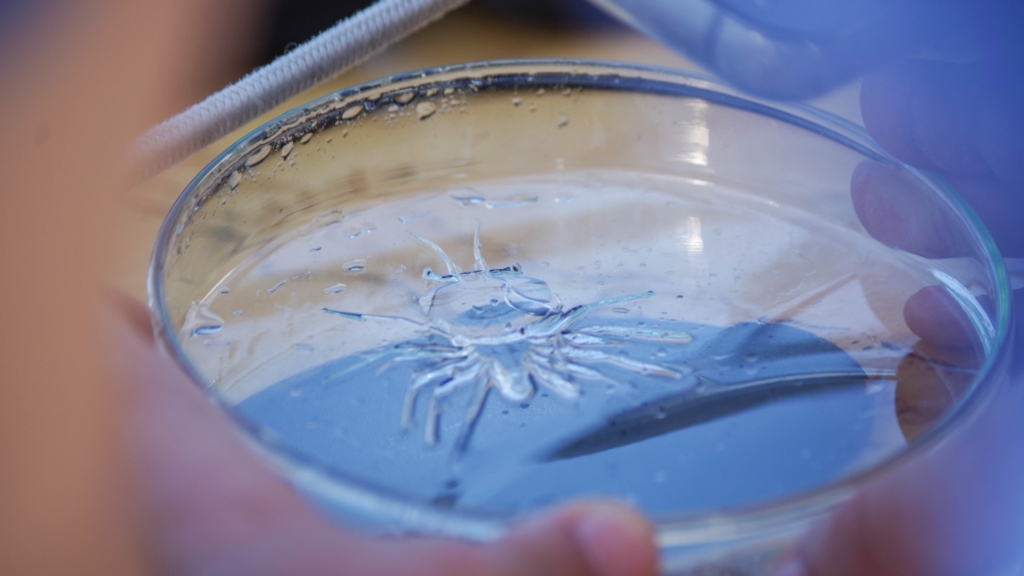

One of the goals was to test the hypothesis that at the edges of these oceanic eddies biological diversity and complexity increases, while at the center, greater competition within the marine microbiome causes certain species to prevail. Once the station was identified and all the necessary material was prepared (bottles, labels, filters, etc.), intense days of sampling awaited us. In one day we would get to work continuously up and down the ship for even more than 17 hours, from the first light of dawn until night. The day’s routine was punctuated by the cast of the rosette (an istrument to sample water at different depths and at the same time record parameters such as salinity, temperature and depth) into the water, by the filtrations and by the spectacular findings in the zooplankton nets. The exciting sightings of whales and other cetaceans alone repaid all the efforts of the day. I remember that the humpback whales, intrigued by that strange floating metal object, circled around us, puffing from time to time to say hello. After days of sampling and moving, the sea began to make itself felt again. We knew that, in the so-called “roaring forties”, the weather would not be stable and calm forever, but fortunately we were able to sample four complete stations.

I remember that, at the end of a day of intense sampling, although we all dreamed of the bed more than anything else, the whole team helped the chief mission assembling some Lagrangian drifters (floating devices used to investigate the movements of currents oceanic) to be launched during the night. These small gestures, in my opinion, made all the difference during the exhausting sampling stations. Obviously there were problems, misunderstandings and mistakes, but each of them, small or large, was faced together, making it easier to overcome.

After the first part of sampling, we began to move eastward, with the wind still in favor and a speed that at times came close to 12 knots, literally “surfing” the waves. I remember for the first time since we left land, I realized how far we had come and how much more we had to go. I realized in those days of travel what the vastness of the ocean around us really was. We were miles away from the world we had left behind. As the chief mission pointed out, for most of our trip, the closest humans to us were those in orbit on the International Space Station, occasionally passing over our head. It was not a metaphor, it was the pure truth, being off the trade routes, off the conventional scheduled air routes and very far from land! Wistful thoughts about loneliness aside, we quickly moved towards our next goal: high resolution horizontal sampling between two fronts, ie at the interface between two eddies, one anticyclonic (clockwise movement) and one cyclonic (counterclockwise movement). The idea was to cross two eddies and do as many surface samples as possible in order to have high resolution in these extremely dynamic and complex environments.

The temperature increased slightly, we left the cold Antarctic waters behind us. We sailed in calmer waters, literally “surfing” the waves, leaning a little to the right and a little to the left guided by the expert hands of the captain and crew members. Seasickness was now only a memory, I began to find the continuous roll of the boat pleasant, to love the silence of the sails. Without the deafening noise of the diesel engine, the sound of the waves breaking on the keel and the creak of the sails moved by the wind, made me feel in perfect symbiosis with the surrounding ocean.

The sampling strategy we had chosen for this second part of the mission was very dynamic and included three different scenarios depending on the conditions we would have faced. All of this required good coordination between us and the scientists left on land, great teamwork and also a good dose of luck! An association of 4 large oceanic eddies were identified, with different characteristics (cyclonic and anticyclonic) which led to the formation of fronts and filaments of different origins, with a different concentration of chlorophyll (a measure associated with primary production, which gives us an idea of the amount of phytoplankton present) and nutrients, all perfect conditions for analyzing the close link between biological communities and the physical characteristics of the water column. At the beginning, the samplings and the work became tight, but everything was now moving like a single well-oiled cog.

The last samples in the rich waters of St Helena Bay and the arrival in Cape Town

I remember very well the arrival near the coast of South Africa, we saw the first ship on radar! A gigantic cargo ship of over 200 meters. A few floating pieces of plastic, an unequivocal sign of our approach towards civilization. The sudden change of smell in the air, the green colored waters, very rich in life compared to the oligotrophic (i.e. poor in nutrients) Atlantic Ocean. We anchored Tara near a beach in St. Helena Bay and then it was a great party. A dive in the cold waters, with some worries for the sharks! The arrival of some curious kayakers passing by, a barbecue on the deck, a few beers, a breathtaking sunset and our hugs. We were wondering what was the thing we missed the most during our long journey and what we would do when we finally got back home. I remember the first phone call home, after almost two months of text messages.

Despite the general euphoria, our mission was not finish yet, we still had a week of intense sampling ahead of us, in a transect off the South African coast. The four stations that we had to sample were part of a historical monitoring series distributed between an upwelling area (i.e., where there is an upwelling current towards the surface) and the continental shelf off St. Helena Bay. Stations already fixed, definitely easier to find than the previous ones, we wouldn’t have to hunt down any “elusive” eddy in the middle of the ocean, no “treasure hunt” to find the maximum of chlorophyll. The upwelling zone, rich in nutrients and biomass, made filtration operations particularly slow and difficult, the filters clogged easily and required particular attention in regulating the system pressure to not to pubreak the tubes and the seals. Being not too far from the coast, to keep us company together with some humpback whales, curious and playful seals flocked around the boat. Being a rich fishing ground, they mistaken us for a fishing boat, hoping to get a few discarded fish from time to time. Unfortunately for them, we weren’t lowering lines, but tools and our nets didn’t trap fish, but tiny microorganisms. After a few hours of gyrations and somersaults on the surface, they left disappointed, only to return the next day with renewed enthusiasm!

The last rosette in the water, the last filter stored in the freezer, the last sampled bottle, the last night at sea and the last moments all ours, only us, Tara and the sea to console us, before arriving on land, before being catapulted back into everyday life. A big party was organized for our arrival in Cape Town, guided tours on the boat for schools and the curious passing by, numerous buffets and dinners with the researchers on board, the heads of the Mission Microbiome and the directors of the Taraocean foundation. All this was a bit strange, it had a strange effect to see so many people boarding, occupying what was our home for two months, but that’s how it works, our expedition had come to an end and the mission had to go on, it was time to pass the baton. After instructing the scientists of the next expedition and helping to reorganize the refrigerators and spaces on board, it was time to leave Tara behind, say goodbye to his fellow adventurers and return home. I don’t want to spend too many words on greetings and the inevitable goodbyes, I prefer to focus on the wonderful people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting and getting to know deeply. I would like to name them all, one by one, 12 extraordinary people thanks to whom my journey became unforgettable: Remi, Cora, Paula, Clara, Ali, Martin, Yves, François, Loïc, David (Monch) and Sophie.